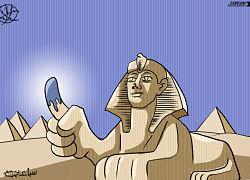

May 23 and 24 marked Egypt’s first free presidential election since the 2011 Arab Spring revolution ousted Hosni Mubarak from over 30 years as Egypt’s unchallenged leader. The mood in Egypt was excited, as many waited hours to cast the first meaningful vote of their lives. There were eleven challengers (two of the 13 candidates listed on the ballot had withdrawn). No candidate, however, won a majority. Because of this, there will be a runoff election June 16-17 between the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi and Ahmed Shafiq, Mubarak’s last Prime Minister. That race kicked off today.

This election is a monumental achievement for those who helped topple President Mubarak last spring. But it is only one step in Egypt’s march toward democracy. The transition from single party rule through the military’s transitional government to democracy will be difficult. Some 30,000 volunteers fanned out to make sure the election was conducted fairly; few violations were reported. There was, however, an underlying fear the military would try to hijack the election, even thought armored vehicles drove through the streets with loudspeakers broadcasting the military’s intention to hand over power to an elected civilian government. Despite these assurances, some fear that the military will not withdraw completely from the political sphere. One analyst predicted Egypt would go the way of Turkey and Pakistan: formal democracies where the military can nonetheless affect significant events.

As the results of the first round were announced on Monday, protesters stormed the headquarters of one of the two finalists. Protests swept through Cairo and Alexandria. The two contenders, Mohamed Morsi and Ahmed Shafiq, are the most polarizing figures in the race. They are seen as extremist candidates – Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood does not have broad appeal with centrists and there is much distrust of those, like Shafiq, who served in President Mubarak’s regime. These protests signal the challenges each candidate faces in the coming weeks. Before the June 16th election, each candidate must amass a broad coalition of support, using only three weeks and the equivalent of $333,000. On one hand, Mr. Morsi’s party is well established across the country. Mr. Shafiq, on the other hand, has the vast network of Mubarak’s outlawed National Democratic party and the security forces behind him. The candidates, however, must paint themselves as appealing to centrists to win the top spot.

The ultimate results of the election spells uncertainty for Egypt’s relations with Israel and the United States. Both candidates, however, seem more inclined to “play the Egyptian street” than Mubarak. This means a foreign policy less inclined to friendly relations with both the US and Israel. Public opinion, under either candidate, will play a larger role. And the public are not as pro-US or pro-Israel as the Mubarak regime generally had been. For example, the Camp David Accords are likely to be reviewed. Already, the transitional military government ended shipments of natural gas to Israel. “Mubarak was dependable” on the international front; the new regime is likely to be less so. The United States and Israel may have to put up with more hostile rhetoric, at least in the interim, from an emboldened public and an Egyptian parliament playing to a different crowd.

Regardless, the true effects will be seen when the results of the run-off election are announced in late June and the military hands over control of the government on July 1. Egyptians have yet to draft and approve a new Constitution, so the president’s powers are not yet determined. Whichever candidate wins will face the challenge of uniting a disgruntled country. But, he will have a strong voice in shaping the Constitution and in driving the relationship with the West. All eyes are on Egypt as it dives into the waters of democracy.