Part 1: What Does “Privacy” Mean?

This is the first post in a three part series examining the issues multinational corporations face in complying with privacy regulations in the U.S. and abroad. This post will explore privacy generally by analyzing privacy as the concept is understood and applied in the European Union, in China, and in the United States. The second post will review two case studies to introduce specific issues multinational corporations have run into in attempting to comply with the three privacy regimes described in the first post. The third post will provide recommendations on privacy strategies companies can implement to mitigate some of the issues identified in the second post. These posts do not attempt to provide an exhaustive list of privacy issues multinational corporations encounter, but they are intended to show the importance of privacy concerns and to highlight the need to confront compliance issues in a proactive manner.

Introduction

“Privacy is a value so complex, so entangled in competing and contradictory dimensions, so engorged with various and distinct meanings, that I sometimes despair whether it can be usefully addressed at all.” – Robert C. Prost

The amount of personal data that is available via the internet is astounding, and that data is valuable. Stores are eager to employ “predictive analytics” in order to understand “not just consumers’ shopping habits but also their personal habits, so as to more efficiently market to them.” The more information a store can obtain about an individual, the easier it is to send them individualized advertisements geared specifically to that person’s needs. For instance, it is now possible, based off consumer purchasing habits, to track an individual’s pattern of purchases and predict when that individual is experiencing a major life change. Once an individual’s purchasing patterns change, the company can respond with targeted advertising to the changed circumstances. Another example is how GPS information in your car has the potential to be shared with businesses to provide targeted advertisements for nearby restaurants.

Although businesses are eager to use information on consumer habits, many people view this kind of information gathering and dissemination as an invasion of privacy. Unsurprisingly, legislators in the U.S. have sought to introduce laws curtailing the ability to collect consumer information without the consumer’s permission. But laws aimed at protecting consumer information must first answer a fundamental question: what exactly is “privacy”? Although it is beyond the scope of these posts to provide an exhaustive list of the ways in which scholars have defined “privacy,” it is important to understand the context in which debates over privacy occur in order to better understand the conflicts multinational corporations face in complying with differing privacy regimes.

Definitions of “Privacy”

One of the earliest and most influential attempts to define privacy in the U.S. was The Right to Privacy, authored by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis. Published in 1890, The Right to Privacy attempted to discern whether the law recognized a “principle which can properly be invoked to protect the privacy of the individual . . .”[1] The article broadly defined privacy to include those things which “concern the private life, habits, acts, and relations of an individual,” those things which do not concern an individual’s fitness for a public office, and those things which do not concern an individual’s acts performed in a public place.[2] Privacy was defined in terms of a right, the “right to be left alone.”[3]

The definition of privacy has greatly expanded since The Right to Privacy was first published. One scholar has recently claimed that “[c]urrently, privacy is a sweeping concept, encompassing (among other things) freedom of thought, control over one’s body, solitude in one’s home, control over information about oneself, freedom from surveillance, protection of one’s reputation, and protection from searches and interrogations.”[4] Other interests identified as falling under the privacy umbrella include the protection of consumer data, credit reporting, workplace privacy, discovery in civil litigation, the dissemination of personal images, or shielding criminal offenders from public exposure.[5]

Privacy is so broad because “[c]onceptualizing privacy not only involves defining privacy but articulating the value of privacy. The value of privacy concerns its importance – how privacy is to be weighed relative to other interests and values.”[6] Such a balancing of competing interests contemplated by the term “privacy” is going to depend on the cultural and historical context in which the interests are examined.[7] For example, a right to privacy for most Americans would include the right to choose the names of their children without any interference. In contrast, it is permissible for French and German courts to determine that a name given to a newborn is contrary to the child’s best interests.[8] Similarly, Americans cleave tightly to the notion that a “broadly defined freedom of the press assures the maintenance of [America’s] political system and an open society.”[9] In China, in contrast, the notion of an independent press is absent; the majority of “print media, broadcast media, and book publishers were affiliated with the [Chinese Communist Party] or a government agency.”[10] Whether privacy means ensuring parents’ ability to name their own children or the right to an independent press, how privacy is defined is largely dependent on cultural influences.

Same Principle, Different Approaches: Privacy in the E.U., China, and the U.S.

The European Union

Privacy laws in Europe have been shaped by the continent’s social and political history. According to James Whitman, a professor of comparative and foreign law at Yale University, the European privacy regime is a direct product of the hierarchical structure of society endemic to Europe’s past.[11] Whitman argues that Europe’s privacy laws are a “form of protection of a right to respect and personal dignity,” focusing on the “rights to one’s image, name, and reputation . . . [and] the right to informational self-determination–the right to control the sorts of information disclosed about oneself.”[12]

The E.U.’s basic regime for protecting privacy rights is found in the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Rights (“E.U. Convention”) of 1953. Article 8 of the E.U. Convention provides that “[e]veryone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.” The Article further states that:

There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

European privacy rights were expanded by the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (“E.U. Data Convention”). Mindful “that it is desirable to extend the safeguards for everyone’s rights and fundamental freedoms, and in particular the right to the respect for privacy,” the E.U. Data Convention sought to ensure that every individual was afforded “respect for his rights and fundamental freedoms, and in particular his right to privacy, with regard to automatic processing of personal data relating to him.”

Privacy in the E.U. is further protected as a result of the adoption of Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (“E.U. Directive”). The E.U. Directive creates a legal floor for the minimum amount of privacy protection member states must afford to their citizens,[13] and it specifically limits processing of personal data.[14] Significantly, the E.U. Directive allows member states to craft laws penalizing parties for non-compliance with its provisions[15] and laws ensuring that processing personal information is only permissible after the subject “unambiguously” gives his or her consent.[16]

One final piece of E.U. privacy legislation relevant to this discussion is the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the E.U. (“E.U. Charter”). The E.U. Charter expressly protects personal data by stating that every person has the right to protect their personal data, to access the data that has been collected about them, and to be afforded the opportunity to rectify any incorrect information.[17] The E.U. Charter further states that any personal data “must be processed fairly for specified purposes and on the basis of the consent of the person concerned or some other legitimate basis laid down by law.”

These four pieces of legislature form the basis of privacy rights in the E.U. They affirm an individual’s right to privacy, which in turn provides a right to “respect and dignity” concerning what personal information is disclosed, the method whereby that information is disclosed, and the ability to control personal information. Multinational corporations operating in the E.U. must be cognizant of the E.U.’s omnibus approach to privacy, which incorporates laws “in which the government has defined requirements throughout the economy including public-sector, private-sector and health-sector.”

The United States

Just as the development of privacy law in Europe was governed by Europe’s historical social context, so too has America’s privacy been determined by its unique social history. Conceived in the context of overthrowing the monarchical control Britain held over its colonies, it is no surprise that privacy in the U.S. is rooted in a deep mistrust of the government.[18] Therefore, the primary privacy concern of Americans might be generalized as protection of the sanctity of the private home against government interference.[19] Because such a privacy concern is defined broadly, U.S. approaches to privacy have focused on specific remedial efforts rather than comprehensive action.[20]

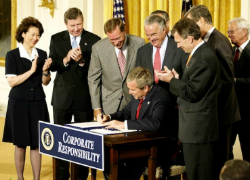

In contrast to the omnibus approach of the E.U. toward privacy protection, the U.S. has adopted a sectoral approach to privacy regulation. The sectoral approach places significance on industry self-regulation while trusting to case law and highly specific legislation to protect particular aspects of privacy law.[21] For example, U.S. Supreme Court cases have recognized a right to privacy regarding family planning[22] and intimacy[23] as “penumbras” emanating from the Bill of Rights despite the lack of an enumerated right of privacy.[24] Industry self-regulation must give way, however, when Congress perceives a failure on the part of industry to adequately protect privacy. Although there are many examples of interest-specific protections, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, one example of specific legislation with particular importance to these posts is the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (“SOX”).

Although SOX amended many government statutes, of primary concern here is the Whistleblower Protection for Employees of Publicly Traded Companies provision.[25] The whistleblower provision delivers employees a cause of action against employer retaliation for the employee’s disclosure of the employer’s illegal conduct.[26] Further, SOX amended the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 to require procedures for receiving whistleblower complaints and ensuring that whistleblowers are able to make communications in a confidential, anonymous manner.[27]

China

China’s privacy policy, similar to the U.S. and the E.U., is the product of its past but, like the E.U. and unlike the U.S., China has focused on omnibus regulations rather than adopting a sectoral approach. To many, China is perceived as an authoritarian government that closely monitors its citizens, effectively depriving them of any meaningful expectation of privacy. However, China has more than 200 laws or regulations referencing privacy in some manner,[28] but the privacy protections are viewed as “more aspirational than descriptive.”[29]

The Chinese Constitution provides citizens with privacy protections by stating that the “personal dignity,” residence, correspondence, and ability to criticize the government are given to the people. In the case of correspondence, the Constitution permits the suspension of private communication “to meet the needs of State security.” China’s General Civil Code also provides for certain privacy protections, including the “right of portrait,” the use of which without the owner’s permission is not permitted. However, despite the promise of these privacy rights, they are frequently violated.[30] As a condition of foreign companies operating in China, the Chinese government requires compliance with its monitoring activities.[31]

Conclusion

The interests protected under the term “privacy” will vary between jurisdictions because of unique historical and social contexts. The E.U.’s omnibus approach to privacy protection traces its inception to the need to protect human dignity, which is furthered only if people have access to and control over their personal information. In contrast, the sectoral approach adopted in the U.S. is the offspring of a mistrust of government intervention; the government should not be permitted to intrude into a citizen’s homes or intrude in how companies operate, so long as companies are acting fairly. China, like the E.U., has adopted an omnibus privacy regulatory scheme, but the protections enumerated in its laws are frequently in conflict with the government’s censorship regime. Although derived from cultural and ideological differences, the differing interests protected by the various privacy regimes have practical consequences for companies operating in multiple jurisdictions. The next post in this three part blog series will use two case examples to illustrate the issues companies must face in operating in the global economy.

Greg Henning is a 3L at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law and a General Editor for the View From Above.

[1] Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Right to Privacy, 4 Harv. L. Rev. 193, 197 (1890).

[2] See id. at 216.

[3] See id. at 195 (internal citations omitted).

[4] Daniel J. Solove, Conceptualizing Privacy, 90 Cal. L. Rev. 1087, 1088 (2002).

[5] See James Q. Whitman, The Two Western cultures of Privacy: Dignity Versus Liberty, 113 Yale L.J. 1151, 1156 (2004) (referring to the types of interests European privacy laws seek to protect) (internal citations omitted).

[6] Privacy book, page 42.

[7] See Helen Nissenbaum, Privacy as Contextual Integrity, 79 Wash. L. Rev. 119, 156 (2004) (“[N]orms of privacy in fact vary considerably from place to place, culture to culture, period to period . . ..”).

[8] See id. at 1216

[9] Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374, 389 (1967).

[10] Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau), U.S. Dept. of State (last visited Feb. 17, 2014), http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2012&dlid=204193.

[11] See Whitman, supra note 5, at 1165.

[12] Id. at 1161.

[13] See Council Directive 95/46/EC, art. 13 1995 O.J. (L 281) 31, 42.

[14] See id. arts. 6-9.

[15] Id. art. 23.

[16] Id. art. 7.

[17] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, art. 8, 2000 O.J. (C 364), 1, 10.

[18] See Whitman, supra note 5, at 1211.

[19] See id. at 1161-62.

[20] See Ryan Moshell, 373

[21] See Anna E. Shimanek, Do You Want Milk With Those Cookies?: Complying with the Safe Harbor Privacy Principles, 26 J. Corp. L. 455, 465-66 (2001).

[22] Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

[23] Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2005).

[24] See Griswold, 381 U.S. 479, 484.

[25] 18 U.S.C. § 1514A (2010)

[26] See Id.

[27] See 15 U.S.C. § 78j-1 (2010).

[28] See Ann Bartow, Privacy Laws and Privacy Levers: Online Surveillance Versus Economic Development in The People’s Republic of China, 74 Ohio St. L.J. 853, 855 (2013).

[29] Id. at 856.

[30] See Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau), U.S. Dept. of State (last visited Feb. 17, 2014), http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2012&dlid=204193.

[31] See David Scheffer & Caroline Kaeb, The Five Levels of CSR Compliance: The Resiliency of Corporate Liability Under the Alien Tort Statute and the Case for a Counterattack Strategy in Compliance, 29 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 334, 389-90 (2011).