Though the term is defined differently in different countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) has come up with a working definition of what constitutes a counterfeit drug in an effort to understand the global implications of counterfeit pharmaceuticals and to facilitate the exchange of information between countries regarding this issue. An estimated 5% of world trade in branded products is counterfeit. Pharmaceuticals are an attractive product for counterfeiting for a variety of factors, the most problematic of which are the difficulty in detecting counterfeits, and lack of a global standard system of enforcement.

The pharmaceutical market is becoming more and more globalized. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that worldwide sales of counterfeit pharmaceuticals exceed $3.5 billion per year. An estimated 80 percent of the active ingredients used in U.S. drugs are made in other countries. 77% of active ingredients for medicines produced in China are exported, and India exports 75% of the active ingredients manufactured there. The problem is even worse in developing countries, where an estimated 25% of medicine sold in street markets is fake.

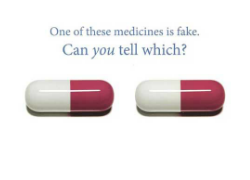

Though the U.S. pharmaceutical industry suffers $20 billion in financial losses annually due to counterfeit drug trade, the dangers of counterfeit drugs are more than economical. Counterfeit drugs can contain dangerous filler and/or substitute ingredients, contaminants, incorrect quantities of an active ingredient, or no active ingredients at all. In the U.S., negligent production at a Massachusetts compounding pharmacy sickened more than 600 people, killing 44, from September 2012 to January 2013. At least 62 people died in 2007 and 2008 after being given contaminated heparin, a blood thinner, made in China. Examples like this are frequent and extreme.

In 2006, the WHO created the International Medical Products Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce (IMPACT). This taskforce aims to foster collaboration between all levels of participants in the global pharmaceuticals market. One suggested method of stemming the flow of counterfeit drugs is the track and trace system. Countries have begun to implement track and trace legislation, or similar legislation to combat the counterfeit drug problem. Where there is no legislation in place, the flow of counterfeit drugs into and out of a country is unfettered, and there is no measure of how tainted the national market for pharmaceuticals may become.

In the U.S., The Drug Quality and Security Act was passed in November 2013, giving the FDA more power to regulate compounded drugs. It is estimated that by 2017, track and trace regulations will be in place that cover more than 70% of pharmaceuticals worldwide. In order for these regulations to be successful, they have to be implemented correctly.

Not only does legislation have to exist, it must deter criminal activity of this sort. Deterrence is nonexistent without adequate enforcement. Enforcement via government regulatory agencies is important, but pharmaceutical companies can contribute by better policing fraudulent use of registered trademarks. Medical professionals can help by staying up-to-date on their knowledge of medicines that have been counterfeited, learning which medicines are most likely to be counterfeited, and by reporting any suspect packaging, labeling, and patient complaints about prescription medicines. Consumers can help by refraining from generating demand for counterfeit drugs by obtaining their prescription pharmaceuticals legitimately. If consumers purchase prescription medications online, they should purchase from Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites (VIPPS). In order for any of these behaviors to be effective, there must be cooperation between participants in the pharmaceutical market. All levels must work together to implement and maintain a solution to this very urgent and dangerous problem.

Katelynn Merkin is a 2L and a Staff Editor on the Denver Journal of International Law and Policy.