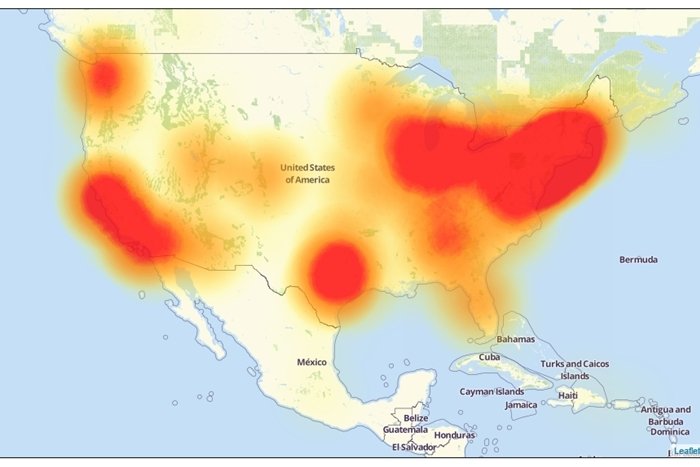

On Friday, October 20th, malicious cyber attacks prohibited access to major websites like Twitter, PayPal, and Amazon in intermittent locations throughout the U.S. and abroad. Experts determined the attacks are the result of a virus that infected thousands of users’ internet-connected devices through webcams and video recording devices. This method of hacking is both complicated and sophisticated, which makes it difficult to prevent within the general population of internet product users.

While both the F.B.I. and the Department of Homeland Security announced investigations into the incident, public response to the attacks demonstrates mounting uneasiness about cyber security. Coming on the heels of the Democratic National Committee hacks this summer, Friday’s attacks raise questions about cyber security and the proper response by both national and international bodies. The Department of Homeland Security did issue a warning about the virus code last week, but this ultimately was not enough to remedy the security gaps in consumers’ devices. Some in the industry have assigned blame to the producers of such devices, but many now contend that the issue of cyber security is an international issue that must have an international solution.

Because cyber attacks of international scope are a relatively new phenomenon, the U.N. Charter does not explicitly provide for a procedure to address their consequences and effects. As such, it remains unclear what kind of responses to cyber attacks would be legal under international law. Most likely an issue of self-defense, article 51 of the U.N. Charter provides that, “Nothing in the present charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations. . . .” Cyber attacks, however, are certainly not “armed” attacks in the traditional sense, so any retribution framed in terms of self-defense may not prove to be a successful argument under the Charter. As international law currently stands, cyber security suffers from a noticeable gap.

Governments could also seek to impose sanctions and countermeasures against the perpetrators of cyber attacks, but this strategy poses an additional issue. Because these attacks are designed to preserve the hackers’ anonymity, attributing the attacks to a foreign government is extremely difficult. Attributions would necessitate an investigation into the level of complicity the foreign government had in the individuals’ hacking efforts, which could range from explicitly contracting for their services or neglecting to shut down suspected offenders. Further, the possible development of automated or “robot” hackings make punishing even individual offenders a complicated affair.

Because cyber attacks are likely to only increase in severity and frequency as technology and hackers become more advanced, the international community may be forced to address the issue in setting a clear legal precedent for the aftermath of incidents like Friday’s blackout.