Here in the United States, there has been a recent uptick in news about the “humanitarian crisis” stemming from children migrating across Central America and coming across the United States southern border. The news reports are less frequent now than they were a few months ago, but over the summer months headlines of the “humanitarian crisis” flooded news services. On June 30, 2014, President Obama released a statement recognizing the “humanitarian crisis” that was stemming from the danger and violence in Central America resulting in the influx of children and individuals crossing the border. But what exactly is causing this humanitarian crisis? The current crisis is more than the current influx in border crossings, decades old problems facing youth in Central America is making the international issues of Central America feel very real here at home. See Maria Baldini-Potermin, A Step Forward and Back: The Border Crisis and Possible Solutions Focused on Fundamental Fairness and Basic Human Rights, 91 Interpreter Releases 1401, 1401-02 (2014).

In June 2014, Vice President Joseph Biden traveled to Guatemala to speak with leaders from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico to discuss the shared responsibility of the region. Vice President Biden was also trying to reiterate the current administration’s stance on the futility of trying to obtain legal status without a proper visa. Minors from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras make up three quarters of the total numbers of migrants coming into the United States. Between last October and August, 63,000 undocumented children were detained at the southern border. Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico, while addressing the situations within their own nations have also pushed back on the United State’s policy, seeking better conditions for the detained children in the United States and criticizing American drug consumption, which makes their nations the staging grounds for trafficking.

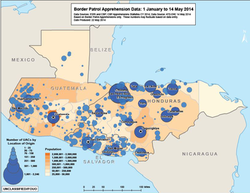

Image Source: pewresearch.org

How does the United States’ deportation policy play into the “shared responsibility” idea? According to the home nations, it does not play out well. Children who are deported back to their home nation face the same violence they were fleeing and if they were trying to escape gang activity, it is often futile. The cycle of violence continues. The Americas have the highest rates of homicides of the UN regional breakdowns, with Central America having the highest rate within the region. There are two points of concentration that generate this violence: gangs and organized crime.

According to a study that Elizabeth Kennedy, a Fulbright Scholar, is conducting in El Salvador, children are migrating to the United States because of fear of gang violence. Currently, over 600 children have been interviewed for the study; these interviews are comprised of basic questions, questions about the child’s neighborhood and gang presence, and finally, why the child wants to go to the United States. Sixty percent of the children have listed gangs or violence as the reason that they want to migrate. After gang violence, the next highest-ranking reason for wanting to migrate to the United States is family reunification. Family reunification makes up 35 percent of the children interviewed, which is interesting because of how low that number is when considering that over 90 percent of these children have a family member in the United States, and over half have a parent in the United States. The numbers that Ms. Kennedy has uncovered around gang violence are particularly striking: 145 of 322 children live in a neighborhood with a gang present, 109 have been directly threatened, 14 have had a family member murdered by the gang, and 32 are so afraid they never leave their homes day or night.

There are common features between Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras that are pushing children, despite the danger, to attempt to migrate across Mexico to the United States. These reasons include poverty, institutional challenges (particularly in crime control), political instability, migration, and destruction of the social fabric. In El Salvador, there has been an active attempt to mitigate the gang violence and two years ago, there was truce designed to protect police and civilians. While initial results of the truce dropped murder rates by 40 percent, killings have since doubled. However, recently five gangs have approached the government wanting to reopen negotiations, but the President is hesitant to follow the gangs’ program. Mexico, meanwhile, has aggressively begun to sweep migrants off “La Bestia,” creating roadway checkpoints, and raiding safe houses along the voyage north. And not surprisingly, Honduras is facing monumental challenges in addresses migration problems when statistics show that 64.5 percent of Hondurans lived in poverty, economic growth is 2.2 percent and San Pedro Sula, is the world’s “murder capital.

Commentators suggest that the real way to solve the humanitarian crisis is to focus on the poverty, violence, and suppression that are preventing the people in these countries from maintaining a healthy livelihood, and to make humanitarian visas to the United States more accessible. It certainly does seem that just trying to stop transport via “La Bestia” is not going to change migration trends or protect the lives of those who are constantly under threat of gang violence. The only way to solve this humanitarian crisis is going to the source.

Alison Haugen is a 2L law student at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law and a Staff Editor for the Denver Journal of International Law and Policy.