(Int’l Bodyguard Service)

There are several forces that deserve credit for the recently reported worldwide decline in pirate attacks – including international naval patrols, industry best practices, and the monsoon season – but no single force has done more to repel pirates that the use of privately contracted armed security personnel (PCASP). With no successful pirate attacks on PCASP-protected vessels reported to date, the use of these private armed guards is sure to continue, if not increase.

Yet as the use of PCASP at sea has proliferated, the international community has failed to keep pace with the trend and ensure that the industry is held accountable for its actions.

Even some in the industry admit that there is much room for improvement. John Dalby, CEO of Marine Risk Management, Ltd., identifies two basic types of maritime security firms. He characterizes the first as the “Reputables,” consisting of well-trained professionals operating in accordance with national and international law.

The other group, which Dalby calls the “So-calleds,” are characterized as being “ill-disciplined,” “poorly trained,” and having “little or no maritime experience.” If his description of these troublesome firms is accurate, the moniker he chose is dubious. These companies are more than merely “so-called” companies; they are actual companies actually patrolling the Indian Ocean.

As for the industry as a whole, Dalby’s feelings are best expressed in the title of his commentary: “The Shambles That Is Maritime Security In 2012.”

The sheer existence of Dalby’s piece sheds a great deal of light on the state of PCASP regulation at sea – a world where private security companies actually want to be regulated, but the international community seems either unable or unwilling to abide.

This role reversal, in which the would-be regulated entity welcomes guidance and the would-be regulator resists, is playing out in the United Nations International Maritime Organization’s (IMO’s) treatment of the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Providers (ICoC).

ICoC is a mostly private regulatory structure consisting of a set of aspirational principles coupled with an external oversight mechanism, the latter still in the drafting phase and expected in early 2013.

At the heart of ICoC is the notion that norms must be externally enforced and that failure to adhere to agreed-upon norms must be met with some sort of coercive punishment. To that end, the Draft Charter for the external oversight mechanism provides for independent auditing of operations, third party grievance mechanisms, and the possibility of suspension or expulsion from the organization in the case of non-compliance.

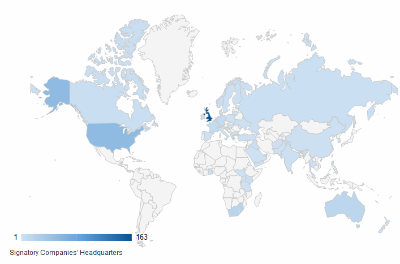

Although ICoC was initially created with terrestrial firms in mind, there has been encouraging and impressive uptake from the maritime security sector. Of the 464 signatory companies to ICoC, 285 of them identify as maritime security companies. This almost certainly represents the vast majority of all firms providing private security in the maritime environment.

According to these maritime security firms, ICoC is highly and directly relevant to the provision of maritime security services.

The International Maritime Organization of the United Nations begs to differ. In IMO MSC.1 Circular 1443 published earlier this year, that organization characterized ICoC as “not directly relevant to the situation of piracy and armed robbery in the maritime domain.” In support of this assertion, the IMO states that ICoC is mere self-regulation and that it was written “only for land-based security companies.”

This first justification is disingenuous and the second is plainly false.

While it is true that no government will assert legislative jurisdiction under ICoC, to call the scheme self-regulation is to give it short shrift. For starters, the initiative was initially conceived by the Swiss government and has the imprimatur of several states, NGOs and industry. Moreover, as already explained, the ICoC contains an external governance mechanism consisting of independent auditors, third party grievance mechanisms, and measurable standards.

The term “self-regulation” evokes images of lip service to the international community coupled with little change in corporate action. Any fair reading of ICoC and the governing mechanism suggests that this is not likely to be the result of ICoC’s ultimate implementation.

More glaringly, the notion that ICoC was developed “only for land-based security companies” is demonstrably false. The preamble of ICoC says that after developing measurable standards and an external enforcement mechanism, the organization would “consider the development of additional principles and standards for…the provision of maritime security services.” In fact, the Draft Charter specifically provides for the provision of maritime security standards in its description of the Board’s responsibilities.

In short, ICoC was drafted with maritime security in mind, it provides for maritime standards in its governing mechanism, and 61.4% of ICoC’s signatory companies provide maritime services. It boggles the mind to think that, in light of these facts, the IMO could conclude that ICoC was written to the exclusion of maritime security companies.

Criticizing the United Nations in this way feels strange. It is strikingly dissonant to see an organization so frequently criticized (at least in the U.S.) for international regulatory overreach openly reject what appears to be an extremely promising step toward a workable regulatory framework for PCASP operating in a legal vacuum.

What accounts for this role reversal? Why does the United Nations seem to be standing in the way of an industry that seems genuinely committed to cleaning up its act? I am afraid that looking into this episode has left me with more questions than answers.

Jon Bellish is a Project Officer at the Oceans Beyond Piracy project outside Denver, Colorado (though all of his views are his own). He has experience in United States piracy trials and just got on Twitter.